- Home

- The Age of Enlightement

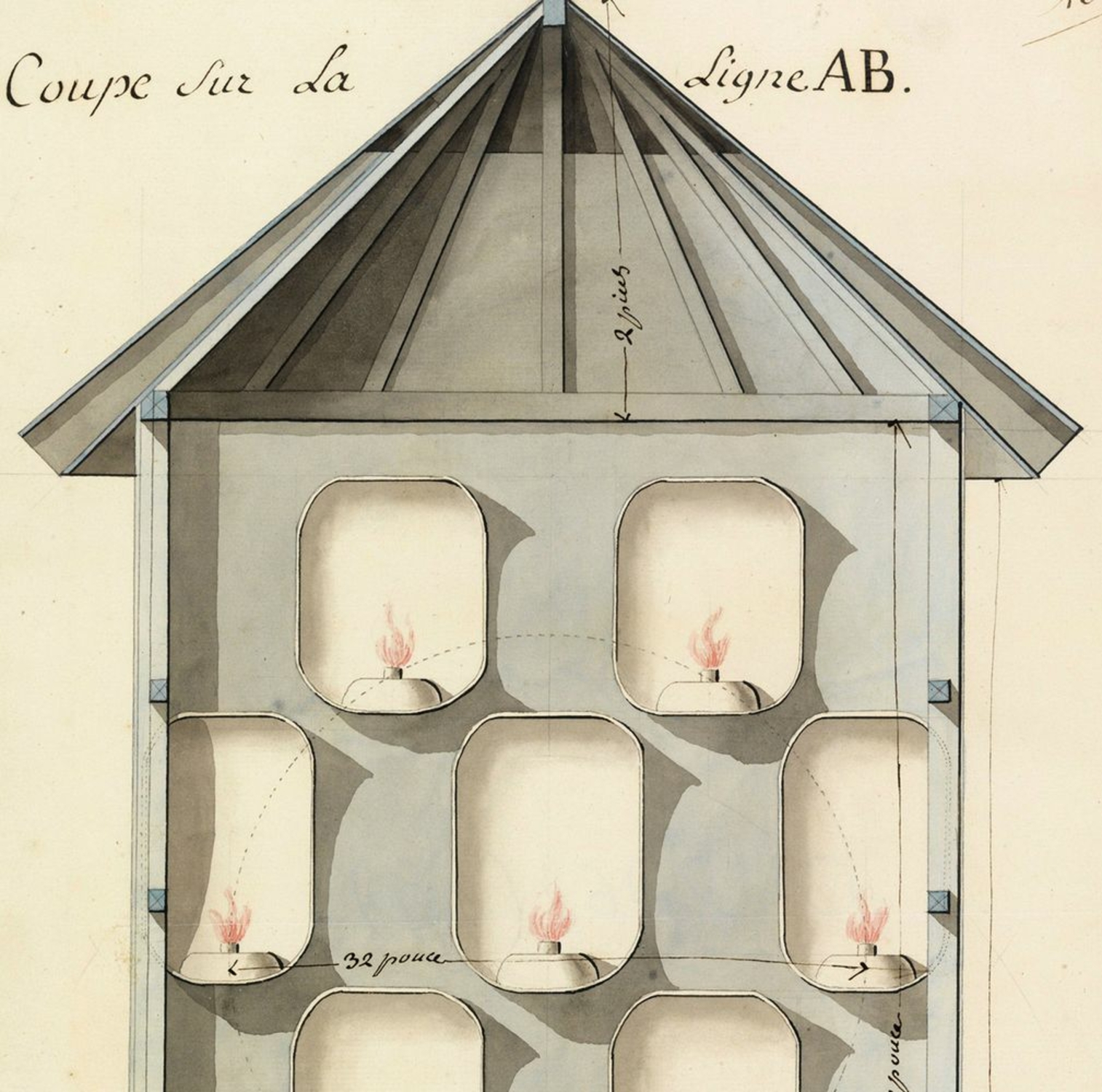

- The Enlightement in the lighthouses

- The English model

In a letter addressed to the English Admiralty in 1724, the intendant Claude Boucher asked straight out for the plans for a burner in order to improve the visibility of the light at Cordouan. He spoke of the technical superiority of the English towers, whose coal fires did not burn out. Boucher's letter is telling – under the Ancien Régime, France had peered at the English coasts, which were far better lit than those of France. But England's superiority was due as much to technology as to the way in which its lighthouses were managed. They were placed under the authority of Trinity House, a corporation recognised in 1514 by Henry VIII. In 1566, Trinity House was granted the privilege of building lighthouses, for which they charged light dues, taxes that were collected in English ports. The Corporation was led by the "Elder Brethren", men and women chosen from the ranks of eminent sailors, as well as from the aristocracy and the world of politics. England developed a public-private management structure for its lighthouses, which stimulated both construction and innovation. The three successive towers built on the Eddystone Rocks, off the coast of Plymouth, between 1698 and 1759 were very much a part of this movement. The first two structures were tragically destroyed. The third, built in 1759 by the engineer John Smeaton, is considered to be the first modern ocean-based lighthouse, and both science and technology played a role in ensuring its stability.