- Home

- The Age of Enlightement

- The Enlightement in the lighthouses

- Financing Cordouan

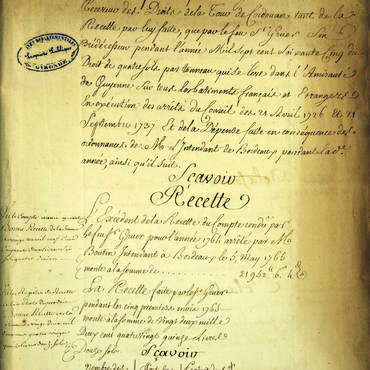

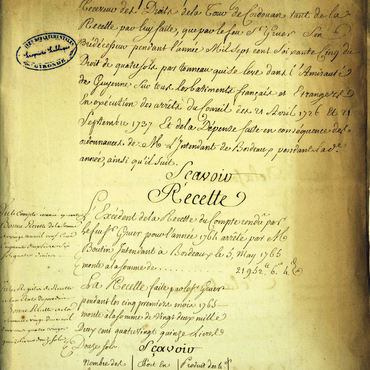

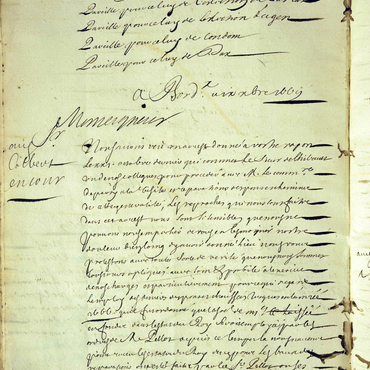

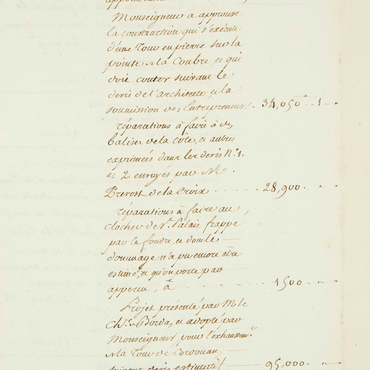

What would we know about Cordouan had the project not become a bottomless pit for public monies? Some of the oldest archives contain documents relating to financing the construction work, to the light dues collected from users, and to the sums paid to both religious and lay keepers. For example, a charter from 1409 gives hermit Geoffroy de Lesparre the right to collect a tax from ships transporting wine in order to pay for the maintenance of the English tower. The plan for the new tower stipulated that its construction and upkeep were to be directly paid for by the king. But the construction of lighthouses in the late seventeenth century – Chassiron et Baleines – introduced a new set of rules. If not the crown, who should pay for maintaining Cordouan? The answer, inspired by the English model, was simple: the user navigating up the "river of Bordeaux" should pay for the light. On the other hand, daily management was not so easy in a country where government administration was not always present. In 1686, based on the design chosen for the Chassiron tower the previous year, the king issued a royal warrant to a certain Masson, huissier at the Parlement de Paris, who was appointed governor of the Courdouan tower. This was a leasing arrangement under which which the king's intendant delegated the collection of light dues. This model, under the terms of which the Conseil de Marine issued orders setting the sums to be paid to the "Cordouan tower tax collector" (a few sols per barrel), remained in force until the French Revolution. The tax collector paid for the upkeep of the light, the keepers' wages and the fees of a chaplain. In the waning years of the Ancien Régime, and with the arrival of Tourtille-Sangrain's reflectors, the management of the country's lighthouses, which up to then had been extremely heterogeneous, became "national", and a single entrepreneur was responsible for maintaining the kingdom's lights, Cordouan included.