- Home

- The Age of Enlightement

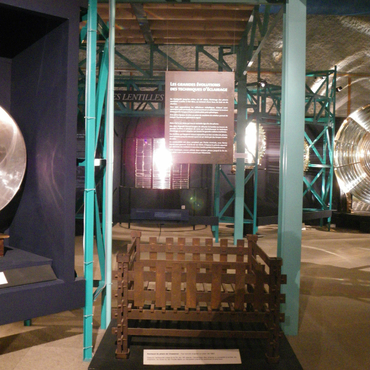

- The Enlightement in the lighthouses

- Oil vs. coal: the sailors' complaints

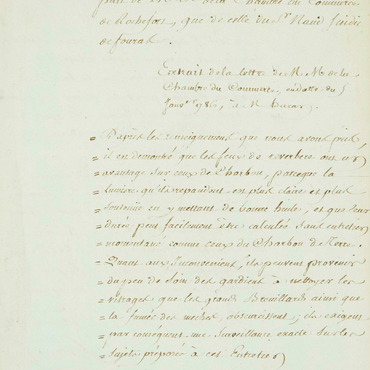

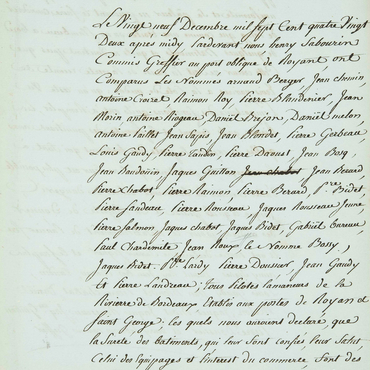

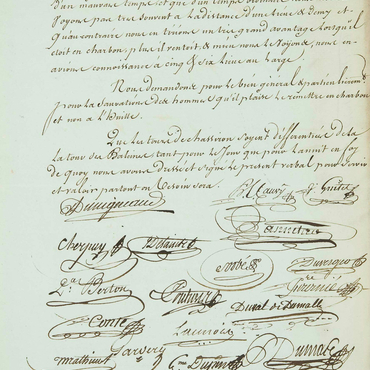

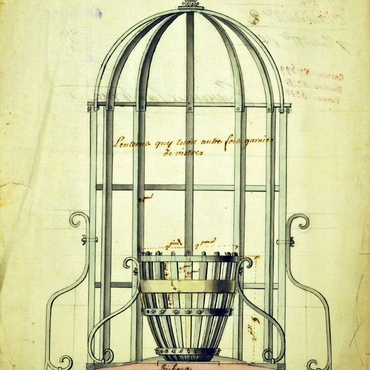

Criticism of Tourtille's reflector lamp, which was installed in November 1782, was not long in coming. On 29 December, the first complaint was registered with the clerk of the Royan Admiralty and then with the Minister of the Navy: "its steadiness and its paleness give it, from afar, the appearance of a star…." Official reports began to pile up, calling for the return of the coal fire. The reflector lights were described as being effective only when the weather was clear. In 1783, a delegation appointed by Charlot de la Grandville, Commissaire Général de la Marine, from among the Bordeaux judiciary and chamber of commerce, was sent to establish an objective report. The result was unequivocal – "the new reflector light does not come close to matching the advantages of coal." According to the supporters of the more modern and economical Sangrain system, it was "a cabal of ill-meaning people capable of being stirred up by a few former keepers of the old light that had to be eliminated." The failure of the keepers to adequately clean the glass was invoked, as well as the oil mixture: a better balance between the turnip and olive oils would make for a brighter flame, while reducing the amount of spermaceti would keep the smoke down. In 1786, the Bordeaux chamber of commerce finally opted for the reflector light. The choice was an economical one: in Bordeaux, it was much simpler to manage and make provisions for the purchase of oil, while the use of coal was contingent on the weather. And yet, de la Granville sent Sangrain a list of essential defects in the reflector light, calling on him to make the necessary changes. The complaints continued until 1790, when a new light was put in place.